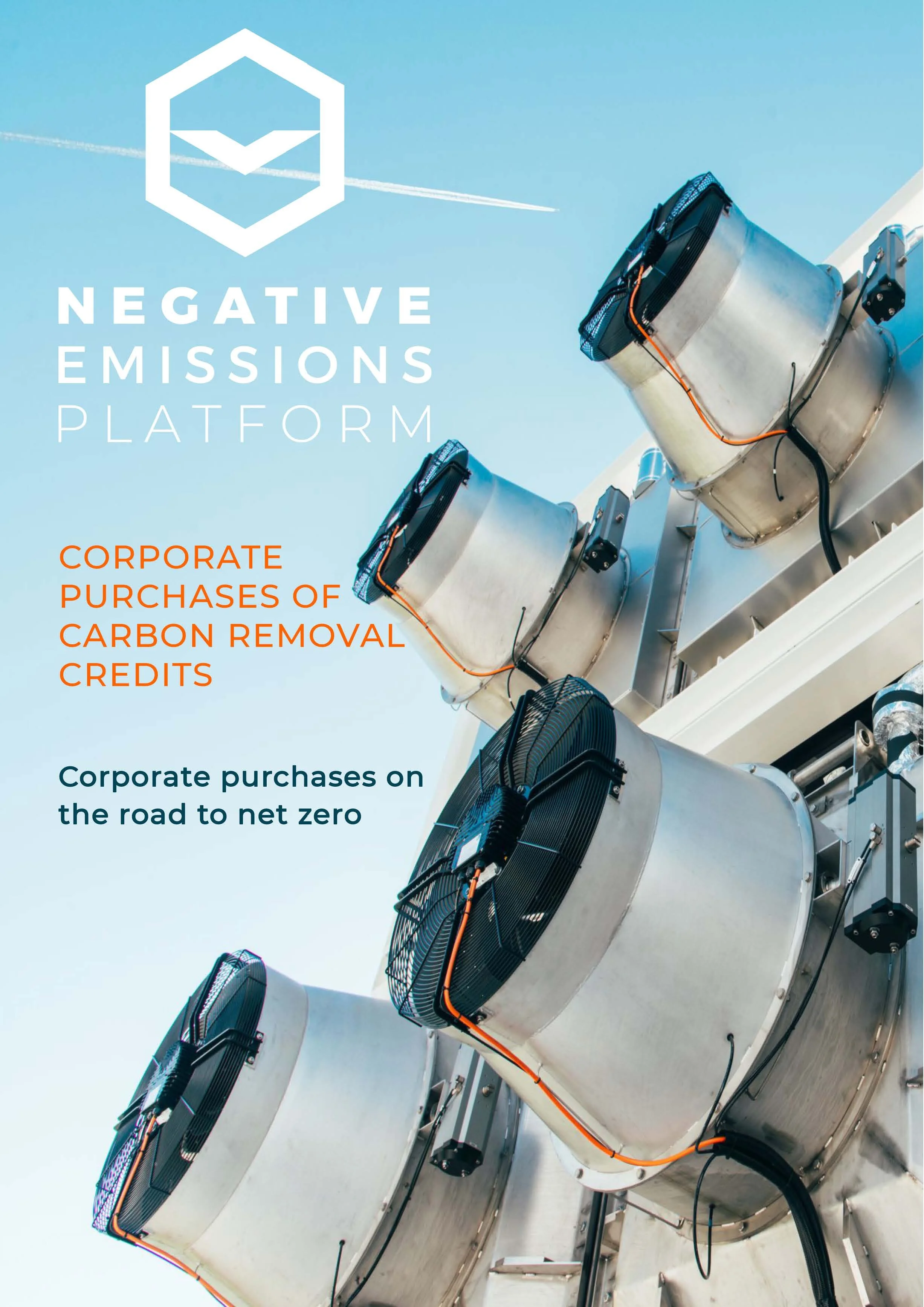

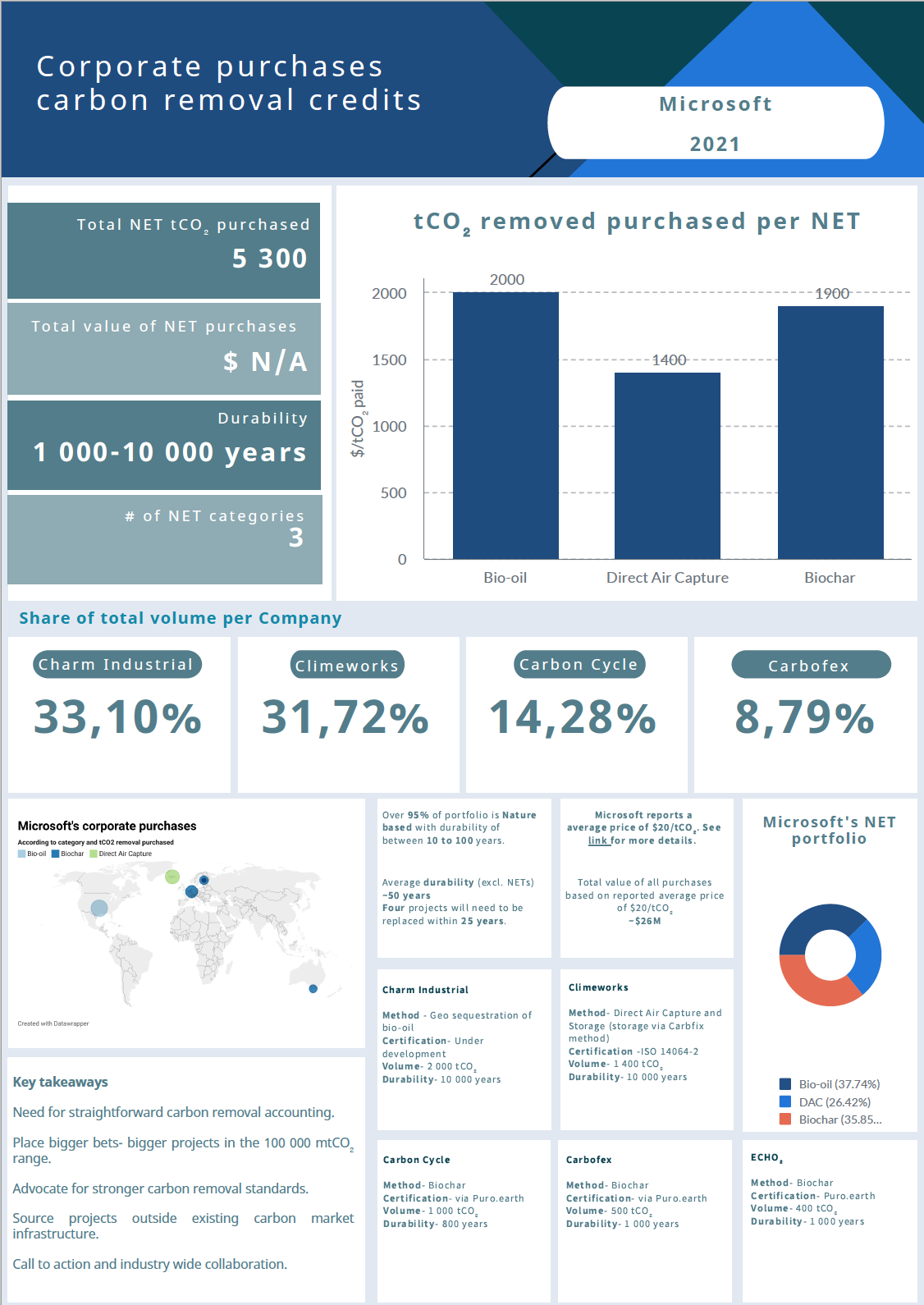

Case study: Microsoft’s purchase of carbon removal credits

In early 2020, Microsoft announced an ambitious target: to become carbon neutral across its whole value chain by 2030, this including activities that are only indirectly related to its day-to-day business. It also plans on compensating by 2050 for its historical carbon emissions, its total carbon footprint ever since the company was created in 1975. The only way it can do that is through carbon removals.

August 27, 2021

While other businesses making similar pledges rely on paying others to protect forests or build solar panels, the ICT giant decided to make a cornerstone of its approach to becoming carbon neutral a concept called ‘carbon removal’. Carbon removals can be loosely defined as the act of taking carbon out of the atmosphere and storing it for decades, or centuries in plants, soil, ocean or geological formations.

To do so, Microsoft had to rely on an external supply of carbon removal. A nascent field made of relatively small companies offering solutions to compensate for the carbon that large corporations emit. While some of these start-ups would limit themselves to selling investments into reforestation projects, others, more technologically-oriented, offer the possibility of taking CO2 out of the air permanently – these are referred to as carbon removal credits.

Microsoft’s effort was exceptional in scale, but also in its transparency. The company’s climate experts rapidly published the result of its ‘request for proposal’, including the main lessons they had learned from purchasing the right to claim the removal of 1,3 million tons of carbon from the Earth’s atmosphere. Last month, they went even further by publishing an outline of ‘criteria for high-quality carbon removals’, a document meant to guide bidders through a new round of procurement launched in July, and which it plans to renew annually.

Creating a framework

This succession of documents and large amount of research done by Microsoft and its associates stems from a fundamental gap in what is already called the ‘voluntary carbon removal market’, the lack of a common framework to describe under which conditions various carbon removal technologies and solutions should operate and, ultimately, how the carbon removed should be accounted for. Something Microsoft’s own expert refer to as the lack of ‘high quality carbon credits’.

In a recent Negative Emissions Platform event, Professor Alberto Arribas, Microsoft’s Sustainability Science Lead for Europe, explained the conundrum: “we do not have a regulatory framework in terms of how we deal with this,” he said, “at present, carbon accounting is done in different ways by different people”. Of the 55 million tons proposed last year to Microsoft by carbon removal companies, only 2 million tons met the set of prerequisites built from scratch by their in-house experts. As a point of comparison, scientists from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) consider that the world should remove some 17 billion tons of CO2 per year at the end of this century.

The recently released Microsoft report on carbon removal assessment criteria, is one of the most comprehensive attempts made to date by a private company to delineate a framework for the purchase of carbon removals, and notably for more permanent, long-term solutions to pull CO2 out of the atmosphere, which would result in ‘high quality’ carbon credits. Two of those, direct air capture and storage (DACS) and biomass-based solutions (BECCS) rely on installations akin to giant fans pulling carbon either directly out of the air, or connected to large apparatuses where is incinerated the biomass waste that is ‘unavoidable’. Animal manure from farms or excess pulp from paper production are some example of natural waste that is, at the moment, hard to recycle in any way. DACS and BECCS installation bind carbon to a solution, which is then injected into geological formations, under the earth.

As heavy industrial processes, DAC and BECCS pre-suppose the construction of large and complex machinery. High-quality carbon removals using these techniques have to account for things that are relatively well-known in large industrial operations, where building a plant is part of the plan: such as ensuring that the activity will not be detrimental to the surrounding ecosystems, engaging with local populations in a way that is respectful of their specific culture, and ensuring that they will economically benefit from the construction of a large installation in their vicinity. All are part of Microsoft assessment criteria. In addition, DACS and BECCS projects have to assess how much carbon will be emitted simply from building the plant and operating it, with reliance on renewable energy rather than fossil fuels to power their processes being a central element of their Microsoft’s assessment.

Quality criteria

Specific to carbon removal by technological means, both DACS and BECCS types of projects will have to determine whether there is a risk of carbon ‘leakage’ from natural wells surrounding the geological formations where CO2 is trapped, and explain how the chemicals used to bind the carbon after it is pulled out of the air will be disposed of safely.

Another carbon removal technique, carbon mineralisation, a process that occurs naturally over millennia, represents the most durable carbon reservoir on Earth, according to experts from Microsoft and Carbon Direct, a consultancy which co-authored the assessment criteria report. Mineralisation can be greatly accelerated by the use of appropriate technologies.

In some cases, and when used as a storage technique as opposed to a way to capture CO2, mineralisation can be attached to a set of commercial models, notably by selling the carbon-storing minerals as construction materials. Because the technology could eventually pay for itself, the development of new projects in mineralisation is presented in the assessment criteria report as a priority for Microsoft.

Negative Emission Platform explores the nascent carbon removal market and the role played by Microsoft in it a report published in July this year (click on the picture to access the report).

But, here again, it is all about being able to mitigate impact on local biodiversity where mineralisation projects are being deployed and engaging with local populations to ensure that any economical development also is socially just. Particular to mineralisation however is the importance and difficulty of quantifying the carbon that has been removed when compared to what would have happened naturally, in other words calculating how normally occurring mineralisation would have been used in human activities over the course of millennia.

Permanence

Finally, for all types of projects, the durability of the carbon storage, or how long it will stay either under the earth, embedded in a construction product or trapped under the ocean, is a central criterion of evaluation. So is ‘additionality to baseline’, or whether investing into a given carbon removal solution will really make a difference when compared to not doing anything, in terms of how much CO2 can be proven to have been pulled out of the atmosphere as a result of a project.

The report also defines criteria of quality for other categories of carbon removal related to the management and exploitation of forests. Unfortunately, Microsoft and others have recently experienced a major setback in this area. The Oregon Bootleg fire in the United States has, in fact, reduced to ashes many tons of carbon removals which had just recently been purchased by Microsoft and other global corporations. The permanence criteria for what are sometimes dubbed ‘nature-based’ carbon removals does not seem to hold.

It is to be noted that, even before the fire set some of Microsoft’s carbon neutrality plans ablaze, the company had already signalled that it would shift to more permanent ways of storing carbon for its next rounds of carbon purchases, and that it aimed to do so by relying on a solid set of principles. It also wants to do so in close collaboration with the European Commission, and Breakthrough Energy - founded by Microsoft’s long-time CEO Bill Gates to advance carbon removal and other climate-friendly tech, has recently signed an agreement to support one of the EU’s own programmes funding green innovation. Professor Arribas hopes that from such a relationship might emerge the regulatory framework that would give credibility to Microsoft’s efforts to build a voluntary carbon removal market. “A lot of the technologies used for carbon removal are being developed in Europe. The EU has a true opportunity to lead in terms of the policy attached to it,” he says.